A lot of what we know about Americans’ beliefs about human evolution has come from periodic surveys by the Gallup Organization—not to ignore priceless polls by the Pew Research Center and the National Science Foundation Surveys of Public Understanding of Science and Technology, (1979–2001), among many others. But more than any other organization, it is the Gallup Poll’s data that have become an empirical icon, data that are widely cited by public opinion analysts, the press, the scientific community and countless others across the globe. [1] Time and again, the Gallup poll has told us that a remarkably stable, sizable plurality of Americans (averaging approx. 45%) appears to believe in a creationist version of human origins; that nearly 40% endorse the theistic supernatural idea that “man has developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God guided this process, including man’s creation”; and that only a very small percentage (13–14%) has accepted the more naturalistic evolutionist position that “man has developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life. God had no part in this process” ( http://www.gallup.com/poll/21814/Evolution-Creationism-Intelligent-Design.aspx).

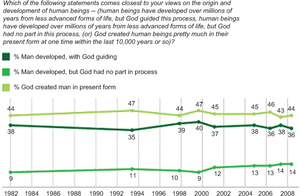

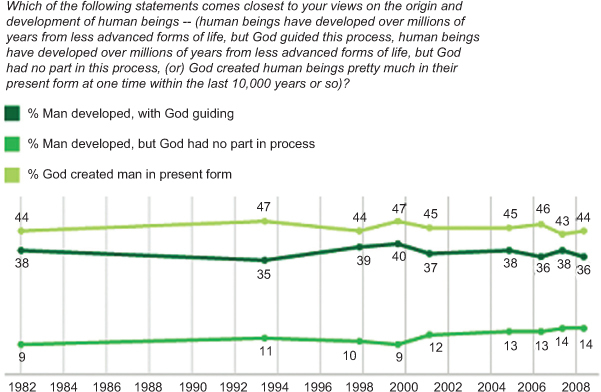

But how well does this standard, widely-cited indicator measure what it appears to measure? With Americans becoming increasingly well-educated over the past quarter century or so, we would have expected to see a significant decline by now in the percentage endorsing the creationist position, for example, especially because level of education is highly and significantly associated with such fundamentalist beliefs. [2] So what accounts for this anomaly? We suspect that there is a significant chunk of measurement error in the standard Gallup question that has heretofore gone undetected and which may explain some, if not much, of the paradoxical stability of Americans’ beliefs about human origins.

In fact, there may be a lot of measurement error to worry about. Data from a recent national survey by the Harris organization (August, 2008) suggests that the widely cited Gallup question may distort what Americans do or do not believe about human evolution; significantly overestimate the percentage of orthodox creationists in the American public; and underestimate the amount of ambivalence, uncertainty and complexity in Americans’ beliefs about human origins. To get at this measurement issue, we designed a modification of the standard Gallup question that added two other explicit response categories: (1) one that allowed respondents who felt unsure of what they actually believed about human origins to express that uncertainty, and (2) a choice that gave respondents who felt ambivalent or who had difficulty mapping their beliefs and cognitions onto the standard, fixed response categories offered by the Gallup item.

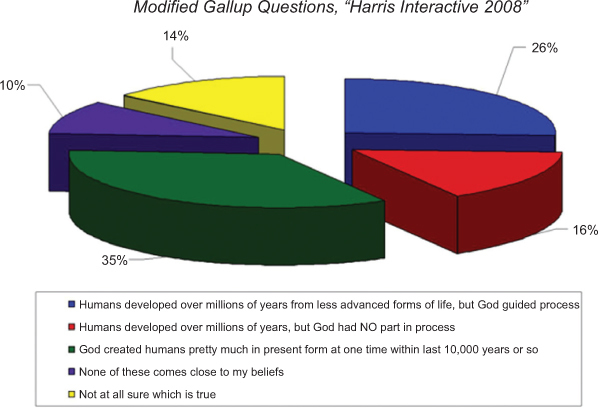

It made quite a difference. Figure 2 tells us that a sizable chunk of the American public is either unsure as to what is “true” about the origin of human beings (14%) or does not think any of the standard Gallup categories even comes close to what they actually believe (10%). So roughly a fourth of the adult population doesn’t fit into the standard Gallup categories when they’re given an explicit set of response alternatives—a finding remarkably reminiscent of other experiments in the literature on offering respondents explicit response categories. In fact, only 5% of respondents in the 2008 Gallup Poll volunteered a “don’t know” or other qualified response. So just on the surface alone these figures tell us that the standard Gallup measure oversimplifies the nature and fixity of what Americans actually believe about the origin of human beings. There’s a lot more ambivalence and uncertainty out there in the mass public’s belief systems.

Notice too that, as compared to the patterns typically produced by the standard Gallup question, offering these explicit response options reduced significantly the percentage of both self-reported creationists (35% vs. 44% in the 2008 Gallup Poll) and theistic evolutionists (26% vs. 36% in Gallup), with little or no effect on the percentage describing themselves as naturalistic evolutionists (16% vs. 14% in Gallup)—indicating that the response-effect is asymmetrical in both magnitude and direction. Respondents who select the option “none of these come close to my beliefs” or “not at all sure which is true” in our modified version of the question would, when forced to choose by the standard Gallup item, most likely fluctuate, randomly or quasi-randomly, between the two “God-is-involved” response alternatives: creationist and theist. Such measurement error may very well mask any changes or trends that might otherwise have been detected over the years. Indeed, we would argue that, had the modified version of the question designed here (or something very much like it) been used by Gallup, the percentage of estimated orthodox creationists in the American public would have declined noticeably over time, just as would be predicted by the ever-rising levels of educational attainment in the adult public.

Nor is this the only measurement-error anomaly that turned up in our data. We also discovered that, even with our more nuanced measure of beliefs, many respondents endorse rather contradictory ideas about the origin of life, indicating there may be even more measurement error to contend with than we’d like to think about. To take but a few conspicuous examples: Over a third (35%) of respondents who chose Gallup’s creationist category in our modified (and purified) version of the question—“God created human beings in their present form at one time in the last 10,000 years or so”— did not believe the creationist tenet that “Dinosaurs lived at the same time as people”; in fact, over half (56%) of such so-called “creationists” actually believed, as modern science tells us, that “Dinosaurs became extinct about 65 million years ago.”

What kind of card-carrying creationists are they? Even better, a solid majority of supposed creationists (54%) think “All animals share common ancestors that gave rise to all the different types of animals that are alive today”—sounds a lot like “descent with modification.” These and other anomalous data patterns (not shown here) tell us that the widely-cited Gallup question may significantly overestimate the percentage of orthodox “creationists” in the American public. Depending on which combination of items we operationalize it with (e.g., selecting the creationist response category in our modified form and believing dinosaurs lived at the same time as people), the percentage of orthodox creationists in the American public ranges from about 20–25% or so—far less than the typical Gallup figure of 45%. Similarly, the percentage of true “theistic evolutionists” is much lower than is suggested by the standard Gallup item, 15–20%, again depending on how it is operationalized (cf. Bishop, 2006, on the influence of question wording on such estimates by various polling organizations:

http://www.publicopinionpros.norc.org/features/2006/aug/bishop.asp).

So what’s the point of all this critiquing of the standard Gallup item? Well, evidently Americans’ beliefs about human evolution in the Year of Darwin (2009) look a lot more nuanced and multidimensional than heretofore suspected. In fact, an exploratory factor analysis we conducted of 60 belief items administered in the August 2008 Harris survey turned up four fundamental dimensions that underlie most beliefs about human evolution, beliefs about: (1) The Purposeful Complexity and Design of Life, (2) God’s Role as Biblical Creator of the Universe and Human Life, (3) The Reality of Genetic Facts of Life (e.g., inherited characteristics of offspring), and (4) the Validity of Scientific Evidence for Evolution [3]. Realistically, we recognize that, while most pollsters cannot afford to insert a battery of such factor-based scales into their surveys of the American public, they can do a lot better than just asking the standard Gallup question. At a bare, practical minimum, we would advocate using the modified version we designed, as it better captures the ambivalence and uncertainty of such beliefs:

“Which of the following statements comes closest to your views on the origin and development of human beings?”

- Human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God guided this process.

- Human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God had NO PART in this process.

- God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so.

- None of these come close to my beliefs.

- Not at all sure which is true.

Replicating this and the standard Gallup item as part of an ongoing randomized, split-sample experiment (in the Gallup Poll?) would tell us before too long (3–5 years) which one better measures and detects changes over time. Better yet, we would advocate going a bit further and using well-designed “random probes” of what respondents have in mind when they choose one of the standard Gallup response categories, because we now know there are creationists and there are creationists; there are theistic evolutionists and there are theistic evolutionists—different apples and oranges within the exact same response categories, producing—we contend—a remarkable illusion of stability in Americans’ beliefs about human origins over the past quarter of a century or so. As we like to say, it’s the validity thing!

See just recently, for example, Richard Dawkins’ (2009, Appendix, pp.429–30) citation of the iconic Gallup data in his recent book, The Greatest Show on Earth. New York: Free Press.

On the basis of sheer cohort replacement alone, we should expect to find a noticeably smaller percentage of the American public today choosing the biblical creationist position and correspondingly higher percentages endorsing the theistic and naturalistic positions, but we do not. The Gallup trend line on beliefs about human origins has been essentially flat for over a quarter of a century and counting. So far we have been unable to identify empirical evidence for any plausible factors offsetting the effects of rising levels of education. Measurement error—both random and systematic— thus becomes the most plausible hypothesis to explain this conundrum.

Factor analysis data are not shown here, but available from the authors.